Professor Wexler

English 436

5/17/10

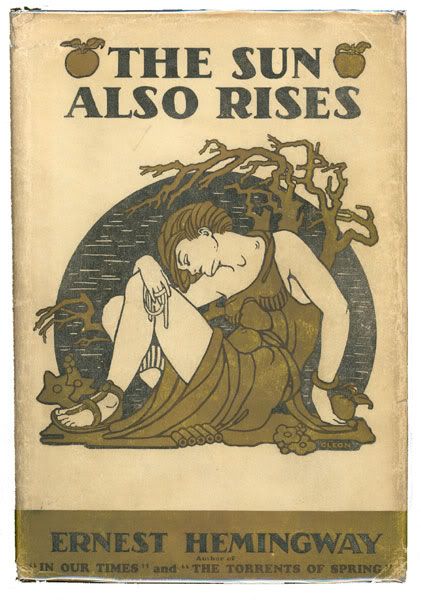

Evolving Gender Roles in The Sun Also Rises

The Sun Also Rises, by Ernest Hemingway, is about the growing emergence of a new type of woman that comes about in the early twentieth century. In the novel Hemingway creates new models for strong American women that had not been used before in literature. Though authors like Henry James had independent women characters in their novels (for example Daisy Miller), Brett has even less regard for her lack of compliance with the societal expectations of her time period than any female character that precedes her in American literature. Hemingway uses the character of Brett to redefine the preexisting gender roles for women and men in the twentieth century by revealing that manly, alcoholic, and emotionally callous women can still be loveable, but in doing so he reinforces the binary system of gender that his character Brett is trying to escape.

Brett has many manly attributes that in the nineteenth century would have made her unattractive to most men, but in the twentieth century her attributes only add to her sex appeal. The attributes include her short hair and the men’s clothing that she wears. The men don’t mind her boyish appearance as Hemingway writes, “Brett was damned good-looking . . . and her hair was brushed back like a boy’s. She started all that. She was built with curves like the hull of a racing yacht, and you missed none of it with that wool jersey” (Hemingway 27). Her boyish appearance causes Jake’s attention to be drawn to the curviness of her body so that the hair doesn’t detract from her womanhood. Instead, it gives Jake a heightened awareness of that womanhood that Brett is striving to push against. In her book Female Masculinity, Judith Halbarstam sheds light on how bending gender roles often reinforces the gender binary because "in a way, gender's very flexibility and seeming fluidity is precisely what allows dimorhphic gender to hold sway. Because so few people actually match any given community standards for male or female, in other words, gender can be imprecise and therefore multiply relayed through a solidly binary system. At the same time, there are very few people in any given public space who are completely unreadable in terms of their gender" (Halbarstam, 948). Essentially, Brett's gender as a female is still readable to Jake and their peers regardless of how masculine she tries to become. Halbarstram would argue that the fact that her womanhood is even in question to begin with proves that the binary system can not be escaped by simply changing ones clothes and hair style.

Unlike most women of the nineteenth century, Brett is always in control of her surroundings and this control gives Brett options that women generally had not experienced. Her independence can be seen in her promiscuity. She makes no apologies for her behavior when she responds to Jake’s accusations about having multiple love interests as she replies, “Oh, well. What if I do?” (Hemingway 27). In Jake’s case her attitude instills respect on his part because he can relate to her unfeminine approach at romance. However, this promiscuity runs contrary to the societal expectations that exists for Brett. In his book, "The History of Sexuality", Michel Foucault discusses how before the industrial revolution religion and society created a "transformation of sex into discourse not governed by the endeavor to expel from reality the forms of sexuality that were not amenable to the strict economy of reproduction" and he goes on to state that society aimed to "banish casual pleasures, to reduce or exclude practices whose object was not procreation" (Foucault, 892). Jake and Brett's relationship is unique because they can not produce children even if they desired to. This is due to Jake's war wound which forces Jake to look at Brett as being more than a sexual object (the wound suppresses his capability to have sex). As a result, their friendship is based entirely on the emotional support that they offer to one another and this makes it impossible for them to conform to the traditional expectations of society.

Jake's feminization, and Brett's promiscuity, are both products of the industrial revolution that forced both men and women's sexual roles to evolve. In her essay, "Sexual Transformations", Gayle Rubin describes the effect of industrialization on sex as she writes:

In spite of many continuities with ancestral forms, modern sexual arrangements have a distinctive character which sets them apart from preexisting systems. In Western Europe and the United States, industrialization and urbanization reshaped the traditional rural and peasant populations into a new urban industrial and service workforce. It generated new forms of state apparatus, reorganized family relations, altered gender roles, and made possible new forms of identity, produced new varieties of social inequality, and created new formats for political and ideological conflict. It also gave rise to a new sexual system characterized by distinct types of sexual persons, populations, stratification, and political conflict. (Rubin, 889)

Brett and Jake are both products of that urbanization that Rubin is referring to in this quote. Both of them have served in World War I (Jake as a soldier and Brett as a nurse) and this exposure to human depravity strips them of their faith in society. Without this inherent faith in society they are able to transcend the societal conventions such as gender roles and matrimony.

Brett is an alcoholic but the attribute does not make her any less desirable to the men around her. They encourage the alcoholic behavior because they wish to impress Brett with their ability to show her a good time. Every chance Brett gets she orders a drink, yet the Count tells her that she has “the most class of anybody I ever seen. You got it.” (Hemingway 59). His praise reflects the evolving gender roles of both men and women as the men acknowledge that a woman who acts (in this case drinks) like a man can still be desirable. Yet it takes her alcoholism for her to be accepted outside of her conventional gender. She is looked at as a tragic drunk who adds "class" to their brutish bar sessions.

Even though Brett is callous and cold with the men that pursue her, she is still aggressively pursued by these men because their desire outweighs their fear. Even when her fiancé realizes that she is cheating on him he remains engaged to her because he feels he understands her fickleness. Her emotional distance from men reminds these men of themselves. Jake shares the strongest connection with Brett and her emotional distance because the two of them are both isolationists. They both are very lonely even though they spend much of their time with people; they find that they can not relate to the joy expressed by their peers and this alienates them. Her coldness redefines her gender role as a woman because it is the men who are expected to be less emotionally attached to the women they date. It was expected that a woman would be forthcoming with her affection but Brett defies that expectation. She juggles men at her whim and refuses to settle for just one.

Her chilly demeanor does not make her any less desirable to Jake. In the critical essay “Brett Ashley: The Beauty of It All” Linda Miller asserts that “Although Jake cannot penetrate Brett physically, he can realize her spiritually, as her eyes become the windows of her soul” (Miller 177). Miller is referring to the cab ride that Jake shares with Brett and how her eyes seem to come alive when they are alone, as opposed to when they are in public and her eyes become flat. Jake being allowed into Brett’s more vulnerable side grants him access to Brett that the others don’t get, and this is furthered by the fact that their friendship is not based on sex. This is evident when Jake goes back to help Brett at the close of the novel. At this point it is clear to Jake that Brett can never be romantically exclusive yet he still desires to be near her because he appreciates her friendship in a purely platonic manner. Hemingway uses their friendship to make a statement that the gender roles of women and men are changing. The fact that both characters in the end have to settle for dysfunction, rather than happiness, shows that Hemingway himself feared this change.

To further illustrate this fear Hemingway creates the characters of Robert and Romero whom are not ready to fully accept those changes. Hemingway writes that Robert “wanted to take Brett away. Wanted to make an honest woman of her” (Hemingway 181) and Brett says Romero, “really wanted to marry. So [I] couldn’t get away from him” (Hemingway 218). Robert and Romero can not handle Brett the way that she naturally is so they wish to marry her so that they can feminize her to meet their standards. The standards were established by their upbringing. It is interesting to note that Romero grows up in Spain, and Robert grows up in the United States, yet their expectations of the female gender remain nearly identical. It is because of those standards that Brett chooses to leave both of these men because she refuses to compromise her sexual identity for them. In the end Brett’s independence does not bother Jake enough for him to stop pursuing her. Essentially, Hemingway uses Jake to contrast Robert and Romero and to make a statement that some men are willing to put their egos aside in order to embrace this new sense of womanhood, even if it means humbling themselves to a position that holds no power. The men who are not willing to accept her take her version of the female gender to represent a third gender, or an un-woman. She is not allowed to take the status of a man, but she does not prescribe to the preexisting female gender roles, so she becomes genderless, and therefore worthless in their eyes. Halbarstam discusses this phenomenon of not belonging to either gender when she wrote, "Ambiguous gender, when and where it does appear, is inevitably transformed into deviance, thirdness, or a blurred version of either male or female" (Halbarstam, 948). By unsubscribing to a particular gender Brett has become "deviant" and her peers (aside from Jack) tend to approach her with caution.

Jake values Brett enough to relinquish any false sense of power that he could have over her because their friendship is not based on sex, it is based on a kinship they share due to their inability to connect with others. In her essay “Life Unworthy of Life? Masculinity, Disability, and Guilt in The Sun Also Rises” Dana Fore writes that “critics have glossed over the complexity of the relationship between Jake’s identity and the stereotypes linking wounds, physical power, and masculine degeneration” (Fore 74).When Jake leaves Paris to go help Brett he is actively giving up his masculinity because he knows in his heart that Brett will never be satiated by him physically (due to his war wound). Hemingway is exploring the boundaries of what it means to be a strong leading male protagonist by creating a character that Todd Onderdonk labeled as a “sensitive, socially passive observer, given to tears and quiet resignation” (Onderdonk 61). Jake knows in his heart that Brett is incapable of loving him but he chooses to help her because they are friends. This aspect of their friendship that is strictly platonic is not understood by society or their peers.

Jake develops a new philosophy regarding gender roles when he thinks to himself that “Women made such swell friends. Awfully swell. In the first place, you had to be in love with a woman to have a basis of a friendship” (Hemingway 137). These thoughts weigh on him for the rest of the novel. J.F. Buckley asserts that Jake handles the friendship with more honesty than Brett, as he writes that “Brett bemoans the loss of such a model relationship, while Jake, in a very telling manner, rejects both the possibility and the desirability of any such arrangement” (Buckley 73). At the end of the story Jake knows that having a romantic relationship with Brett is just a “pretty” idea because they could never be together due to his lack of sexual competence and her lack of capability to emotionally connect with others.

Hemingway affected how Americans viewed their evolving gender roles. Sara Pendergast writes about the influence of the novel in her reference book St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, “The book was amazingly influential: young women began talking like the flippant heroine, Brett Ashley, and young men started acting like Jake Barnes . . . muttering tough-sounding understatements and donning the repressive sackcloth of machismo” she goes on to write about how the novel inspired Hollywood “icons such as John Wayne, Charles Bronson, and Clint Eastwood” (Pendergast 387). It is ironic that Jake inspired macho icons with his misogynistic dialogue when if one looks closely at the character one can see that Jake is vulnerable and in some ways devoid of manhood (for example his war wound that eliminates his sex drive). Again, by trying to create a character like Jake who behaves contrary to the typical male gender archetype, Hemingway unwittingly established a new archetype. The new male definition includes vulnerability, but it does not free the men from their old roles as protector and provider. In other words, Hemingway redefines manhood to include more feminine attributes, but he does not release men from the chains of their past roles so that in essence the new man has even more expectations set upon him. These new men would be responsible for being not only tough, but also sensitive.

With society changing, both in America and in Europe, what is deemed to be acceptable also changes; in the middle there is confusion as to how much of the older gender roles are worth keeping and how much should be thrown out. The Sun Also Rises is Hemingway’s attempt at explaining how that confusion is experienced by his generation, but unfortunately he offers no solutions. Instead, he unwillingly continues to promote the gender binary system that was so clearly established before he was born by creating characters who defy that binary, only to be misunderstood and treated miserably by their peers. His novel is a warning about how evolving gender roles threaten to ruin the happiness and comfort of those who can not fit within the status quo.

Works Cited

Buckley, J.F. “Echoes of Closeted Desires: The Narrator and Character Voices of Jake Barnes”. The Hemingway Review 19.2 (2000): 73. Literature Resource Center Web. 1 October 2009.

Foucault, Michel. "The History of Sexuality." Literary Theory: An Anthology. Second

Ed. Julie Rivkin & Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004.

892-899. Print.

Fore, Dana. “Life Unworthy of Life? Masculinity, Disability, and Guilt in The Sun Also Rises”. The Hemingway Review 26.2 (2007): 74. Literature Resource Center Web. 1 October 2009.

Halberstam, Judith. "Female Masculinity." Literary Theory: An Anthology. Second Ed. Julie Rivkin & Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004. 935-955. Print.

Hemingway, Ernest. The Sun Also Rises. 1926. New York: Scribner, 1996. Print.

Miller, Linda. “Brett Ashley: The Beauty of It All”. Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism. Vol. 203 (1995): 170-184. Literature Resource Center Web. 1 October 2009.

Onderdonk, Todd. “Bitched: Feminization, Identity, and the Hemingwayesque in The Sun Also Rises”. Twentieth Century Literature 52.1 (2006): 61. Literature Resource Center Web. 1 October 2009.

Pendergast, Sara. St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture. Detroit: St. James Press, 2000. Print.

Rubin, Gayle. "Sexual Transformations." Literary Theory: An Anthology. Second Ed. Julie Rivkin & Michael Ryan. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2004.

889-891. Print.

instagram takipçi satın al

ReplyDeleteinstagram takipçi satın al

instagram takipçi satın al

instagram takipçi satın al

instagram takipçi satın al

instagram takipçi satın al

instagram takipçi satın al

perde modelleri

ReplyDeletesms onay

MOBİL ÖDEME BOZDURMA

https://nftnasilalinir.com

ankara evden eve nakliyat

trafik sigortasi

dedektör

website kurma

ASK ROMANLARİ

SMM PANEL

ReplyDeletesmm panel

iş ilanları

instagram takipçi satın al

hirdavatciburada.com

beyazesyateknikservisi.com.tr

Servis

tiktok jeton hilesi